So many questions spring to mind when I look at this photo of an African lady sporting full Victorian-style dress in the hot desert heat. Some more frivolous than others, like: is she hot, or deceptively cool? Did she design it? Did she make it herself? Is she a fashion designer? Does she dress like this all the time? Where is she going – somewhere special or just to run errands? Maybe she’s in Bridgerton. Perhaps I should start dressing more fancy at my desk. Those kinds of things.

All reasonable questions and thoughts I was excited to explore. What I was least expecting to discover was that the story of this impeccably dressed woman and her unique cultural identity is linked to the biggest genocide in modern history, before the Holocaust.

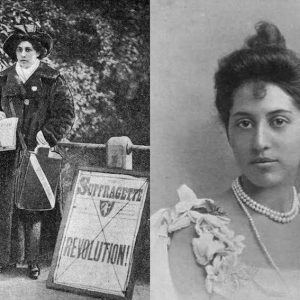

These ladies belong to a generation of the Herero tribe, a cattle-breeding community from Namibia. Their Victorian-era style dates back to a time in their history when German colonisers stole their corner of south-west Africa, and made them wear Western clothes, before exploiting and almost wiping them out.

Why would the modern-day Herero dress like their Victorian-era oppressors? As a way of acknowledging their forefathers’ suffering and accepting their past. It’s also said it helps them to gain resilience and grow stronger. “Wearing the enemy’s uniform will diminish their power and transfer some of their strength to the new wearer,” anthropologist Dr Lutz Marten who specialises in the Herero people told The Independent.

Their backstory is hard to comprehend (I talk about it more a bit later). Yet, there’s no doubt their modern-day Victorian-style ensembles are incredible; a feast for the eyes. They’re called Ohorokova in Otjiherero, the Herero language. They feature beautifully cut Empire line dresses with as many as seven layers underneath to create shape, and puffy ‘gigot’ sleeves – full at the shoulder, tight to the wrist – typical of 19th century western fashion. The horn-like hats are a Herero addition. Made with contrasting fabrics, they’re designed to honour the cattle their communities depend on so highly.

From their wedding day onwards, they dress this way every day of the year – even in temperatures up to 50˚C – for any occasion from shopping to celebrations. The more important the activity, the more elaborate the design. Seeing as outfits for weddings and funerals are worn only once, they’re designed with the specific wearer’s personality in mind. This makes Herero gatherings as much about fashion as the event.

Over time, the Herero women have become more creative with their elaborate homemade outfits. Fabric and colour choices have become more bold, even including patchwork and lace. For the more skilled women, this is a way for them to express their talents. They even create miniature doll versions of themselves dressed in their elaborate outfits which they sell to tourists and craft organisations.

Before the Germans arrived in this part of Africa, most Herero were bare-breasted and wore front and back leather aprons, made from sheep, goat or game skins. They were known for their ostrich shell-embellished overskirts and metal beadwork, as well as the brass, copper and carved horn cuffs worn at their wrists and ankles.

“Instead of the Herero being topless and barely covered, which would offend the modest attitudes of Victorians at the time, they wanted them to be covered up,” Tim Henshall, a British tour operator who has visited the region for nearly two decades and got to know some of the women, told CNN.

Here’s where things turn unimaginably nasty.

Soon after the Germans arrived in Africa, treaties made with the natives were violated. The Herero people were used as slave labour. Women and girls were routinely raped by German soldiers and their land and cattle were randomly confiscated and given to German settlers. In 1904, when the Herero began to fight back against their oppressors, a German colonial general issued an “extermination order”.

German soldiers forced Herero people into the desert, poisoned wells and confined thousands in concentration camps. Some 65,000 Herero died, mostly of starvation, dehydration and disease, reducing one of the region’s main ethnic groups to a population in the low tens of thousands. During the violence, many fled the country.

Today, there are over 250,000 Herero people in Namibia, Botswana and Angola. In 2004, at the 100th anniversary of the start of the genocide, a member of the German government officially apologised for the genocide in a speech: “We Germans accept our historical and moral responsibility and the guilt incurred by Germans at that time.”

Yet no compensation has been offered and 70 per cent of Namibian farmland is still controlled by whites and socially disadvantaged black or coloured citizens own only 16 per cent of the land. It’s unsurprising protests are ongoing. Recent years have also seen a surge in young Herero designers, models and activists rising up to fight for justice and celebrate their heritage.

The Herero are also the subject for various artists including two photographers, whose work I feature in this post: French photographer Charles Freger who photographed them in 2007 – see his photos here; and Jim Naughten, who shot them for a book called Conflict and Costume: The Herero Tribe of Namibia.

The Herero are also the subject for various artists including two photographers, whose work I feature in this post: French photographer Charles Freger who photographed them in 2007 – see his photos here; and Jim Naughten, who shot them for a book called Conflict and Costume: The Herero Tribe of Namibia.

Finally, if you plan to see the Herero ladies for yourself, Namibian Tourism says you’re likely to spot them running daily tasks on a walk through Windhoek, the capital city of Namibia; or in the town of Okahandja for the annual Herero Festival on Maharero Day, which takes place every year on the Sunday closest to August 23, which marks the day Herero chief, Samuel Maharero’s, body was returned to Okahandja in 1923.